Madame Adelaide

Princess Marie Adelaide de France was the fourth child of Louis XV, after her twin sisters Elisabeth and Henriette and the Dauphin Louis Ferdinand. She was raised at Versailles with her elder sisters, very much in the shadow of her brother. It was naturally assumed that she and her sisters would marry - marrying to cement alliances was the only real purpose of a princess - and, true to form, her elder sister Elisabeth was married off to Spain a few months after she turned 12. Then – the marriages stopped. It was a combination of factors: Louis’ true fondness for his daughters (especially when they were younger); a dearth of suitable Catholics in a Europe that was also heavily Protestant; no urgent need for new treaties and new allies (Spain was already in the bag); laziness on the part of the king, and finally the desire of the sisters to stay in the most magnificent palace in the most magnificent country in the world – what else could compete with Versailles?

So Adelaide and her sisters never married. With the death of her sister Henriette in 1752, she became known as Madame and she ruled over her younger sisters; by all accounts she had a very strong personality and was quite intelligent. As they grew older, she and her sisters became increasingly marginalized at a Court that fluttered around her father and his mistresses (whom they invariably despised), and eventually they became figures of pity and objects of fun.

So Adelaide and her sisters never married. With the death of her sister Henriette in 1752, she became known as Madame and she ruled over her younger sisters; by all accounts she had a very strong personality and was quite intelligent. As they grew older, she and her sisters became increasingly marginalized at a Court that fluttered around her father and his mistresses (whom they invariably despised), and eventually they became figures of pity and objects of fun.

|

This is a pretty portrait of Adelaide when she was younger, by Nattier who did a whole slew of portraits of the royal family. It's dated to 1756, so she would be 24, though I think she looks younger. She's "making noeuds" - knots - I am not quite sure what that means, but it sounds like one of the endless, needless and unnecessary pursuits she was often (forced to be) engaged in. I like the directness of her gaze; there is something almost defiant yet resigned there. |

|

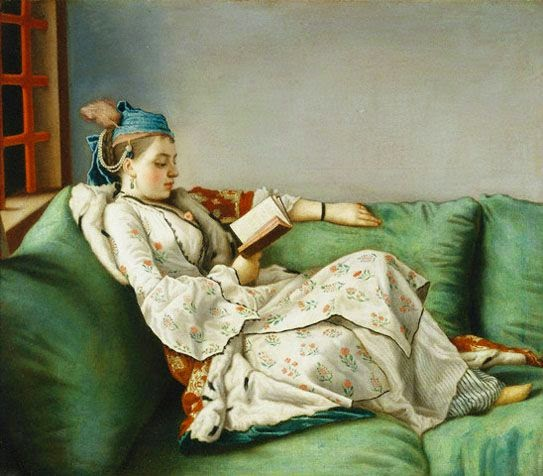

This is a really interesting portrait of her dressed "a la Turque" which was all the rage in the middle of the 18th century. It's by Etienne Liotard and dated to 1753, so Adelaide would have been 21. I love this painting and it doesn't fit at all with my image of her and who she was supposed to be - she's lounging, for goodness sake! |

|

This magnificent portrait of Adelaide, full of symbolism and majesty, painted in 1787, is by Marie Adelaide Labille (who features briefly in The Enemies of Versailles - she's the daughter of Labille's shop owners where Jeanne briefly works). She's standing in front of a medallion depicting her parents and her nephew Louis XVI. |

I really enjoyed writing from Adelaide's perspective; she was the ultimate guardian of the old world of Versailles with all its rules, rituals and intricacies. She would have honestly believed that she was living the most perfect life, in the most perfect palace in the world, and all the changes that happened over the course of her life would have been very distressing for her. I also liked the chance to get inside the daily life of a princess at Versailles in the 18th century, with all its mundaneness and restrictions. I could only find one book devoted to her and her sisters' lives, Mesdames de France, by Bruno Courtequisse, and it was very informative about their education, the etiquette, the expectations. Etiquette differed at different royal palaces, and one fact I really liked – and which captures the extreme strictness of their lives – is that when they were at Fontainbleau with their family, Adelaide and her sisters were not allowed to eat in the presence of a man, even their own brother!

I had a lot of fun writing Adelaide – making her as obtuse and insular as I could, to represent all the narrow insularity and extreme snobbism of Versailles – but I also feel a little guilty about the way I portrayed her. As noted above, she was by all accounts quite intelligent, and quite talented in her knowledge of languages and music, but I fell into the all-too easy trap of making fun of silly, fusty old spinsters. So in some ways I regret my characterization, but it was just too tempting, especially opposite Jeanne, the ultimate outsider, and Marie Antoinette, also an outsider.

I had a lot of fun writing Adelaide – making her as obtuse and insular as I could, to represent all the narrow insularity and extreme snobbism of Versailles – but I also feel a little guilty about the way I portrayed her. As noted above, she was by all accounts quite intelligent, and quite talented in her knowledge of languages and music, but I fell into the all-too easy trap of making fun of silly, fusty old spinsters. So in some ways I regret my characterization, but it was just too tempting, especially opposite Jeanne, the ultimate outsider, and Marie Antoinette, also an outsider.